Your “Constants” Are What Give You Energy And Hope

On this blog we ponder some things that intentional communities like monasteries and housing co-ops and artist’s residencies do well, that we can adapt as individuals. Such places have a strong sense of purpose — they’ve sorted their signals from the noise — and they have systems in place to make time for pursuits like studying, making art, or spending hours in contemplation.

One of the ways they do that is by having consistent routines. But a residential community with a good system in place (processes are clear, written down, and reviewed and revised regularly), also has people who can fill in for other people without much trouble. If I am sick and can’t do the dishes, someone else in the community can probably cover for me that day.

But especially with consistent routines, we as individuals have to approach this differently.

The challenge for individuals is that we are far less likely to have back-up. If you live alone, and you get sick, we all know, sadly, that there is no dish fairy who magically swoops in to start the suds.

If you live with others, especially if you live with young children, people with varying work schedules, or people who are disabled, there might not be anyone else who can cover.

If you yourself are dealing with disability or a chronic illness or a season of life that leaves you with little time or energy, it’s hard to know where to even begin with a routine.

Defining your “constants” will help greatly. Some things to keep in mind about constants:

1) Constants for individuals work differently from constants for communities — as individuals we don’t have the same resources, so we need different strategies.

2) Constants are highly personal. It is crucial to sort your signals from the noise, when you figure out what your constants really are.

Your constants are not about doing what other people think you should do. Your constants are the things that you know, from your own life experience, make you, personally, feel better when they are done.

Your constants are the things you do for yourself that give you energy and a sense of hope.

For Communities, “Constants” Are the Routines That Keep Them Running Smoothly

Intentional communities have well-defined routines — assigned tasks and people assigned to do them — to keep the place running smoothly. The housing co-op I lived in as a student was pretty much always clean. I felt well cared-for when I came in. The same with retreat centers I’ve stayed at: they are kept clean and uncluttered; there is always a nice dinner. This is because they have what I call “constants” — things that got defined as important, and routines and processes set up and prioritized so these things get done. This is how rooms stayed clean, and meals were on the table. And: communities can draw on a lot of people to get these things done.

We can also use routines in our homes. But individuals or small households simply don’t have the backup that larger groups do, so your routines, as an individual, are more precarious than those of a community.

So, as an individual, how do you set things up to help yourself feel well cared-for? And what if routines have never come naturally for you? What if you feel slightly ill when you see all that external advice on things one ought to do around the house, or the things that one ought to do to stay physically and mentally fit, or — horrors — all of the above? Who has the time?

As individuals we need “constants” too, but we have to think quite differently from standard advice about routines, habits, and task lists.

For Individuals, “Constants” Are the Things That Keep You Running Smoothly

Think of your life in terms of “constants” and “variables.”

Constants are the things you regularly do, that make you feel better. Sometimes these can indeed be household routines, but not always.

Variables are all the things that come up: life’s little surprises. (Surprise! My car is in the shop for the rest of this week! So much for my errands. Routines for individuals are indeed more precarious…)

This is tricky, though, because if there is one area where there is a lot of noise, it is the fire hose of advice from family and friends, from the media and from online sources (like this one! yes, I see the irony here….) about what we “should” be doing.

If you are sorting your signals from other people’s noise, and your own inner noise, you need to understand specifically what it is that truly energizes you, that makes you feel supported, that gives you a sense of optimism and hope about your life and your future. This is very personal, highly individual!

Your constants need to be ones that really resonate for you, and that you know from your personal lived experience, will make you feel better.

Your constants will not be the same as mine.

What are the things that make you feel like life is good or at least tolerable if they are done; and that throw you for a loop if they are not done?

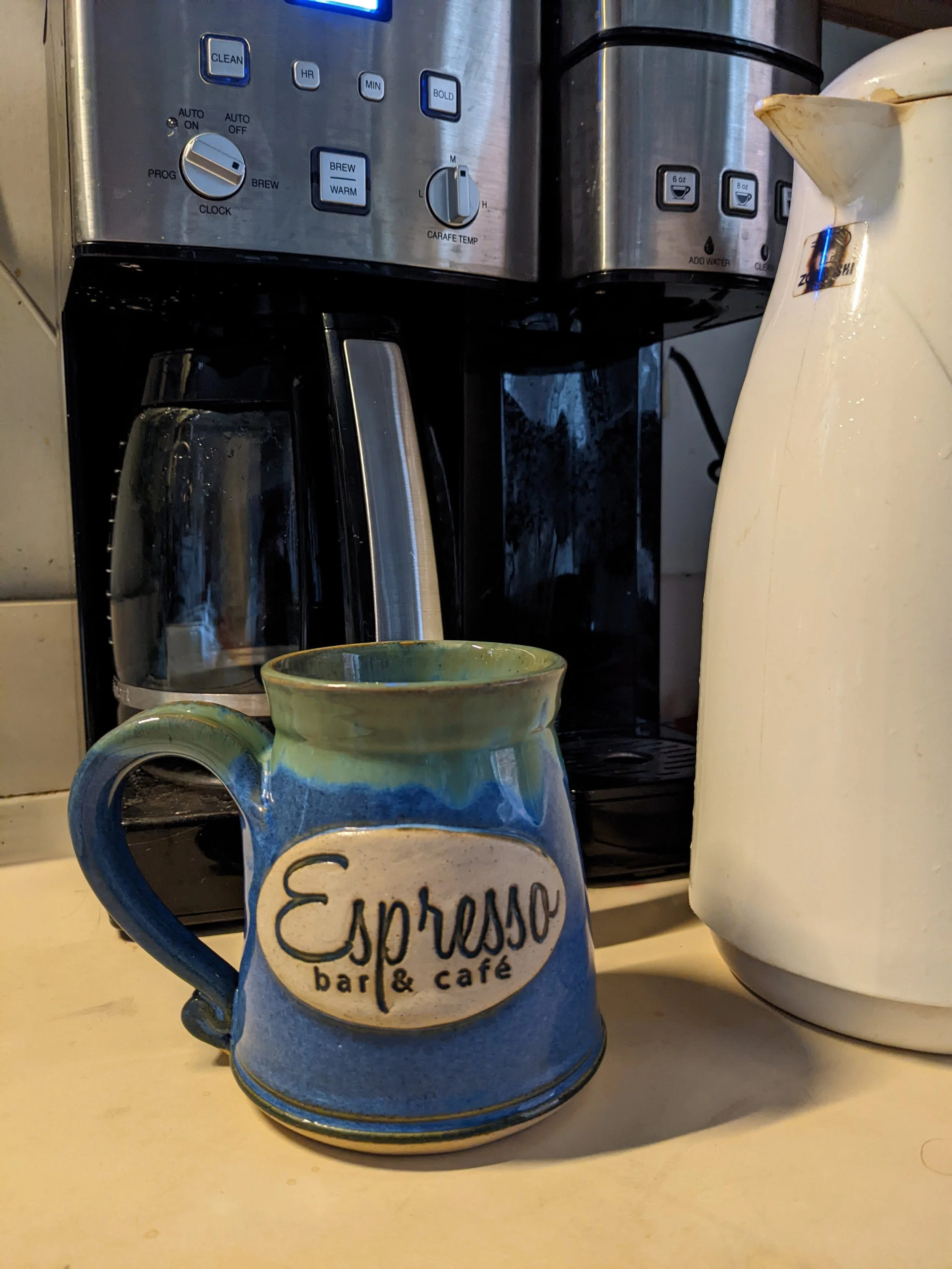

Here’s a core constant for me: I need to be able to get up in the morning and press the button on the coffee machine, and have coffee come out. That’s a constant. If I forget to set up my coffee pot the night before, my morning begins with frustration and stress, because I don’t have the brains to make coffee before I’ve had coffee. It’s like trying to find your glasses when you can’t see, and you misplaced them. Frustrating.

It is really good to know your constants AND to write them down, in your personal framework, for two reasons:

1) When we are sorting our own signals, other people’s ideas about what should be a constant can get really noisy. Be very clear on YOUR constants.

2) if you know what your constants are, and you are going through a busy or stressful season in your life, you know if nothing else, the constants are what you’ll prioritize — because your constants are what give you some much-needed energy and hope.

Separating Your Constants from Others’ “Shoulds”

Constants are highly personal. I should exercise more. I should dust more. I should floss more. Sure; and we should have world peace, and everyone on this planet should have access to clean water, decent housing, and enough to eat, too, right?

But I’m not going to have the bandwidth to act on difficult things if I’m racing around looking for coffee.

Your constants are the things that give you a deep sense of feeling cared for. Your constants help you keep your emotions on an even keel. Your constants energize you and give you more optimism and hope.

Then you can go forth and tackle more difficult things. You can make your art. You can write grant applications in your multi-year campaign for low-income housing in your community.

But it is important, before you do demanding things, that you feel well cared-for. Your constants are what it means to put your own oxygen mask on first. Your constants are what it means to love yourself, so that you can love others with an open heart and without making yourself into a martyr. (A lifestyle of pushing ourselves to help others without attending to our own needs is a recipe for illness and resentment.)

One way to identify your constants: if you say, “Well, at least I did xyz today,” that might be a constant. “Well, at least I had some coffee and got some writing done…”

Some of my constants right now are:

writing every morning before work

a very minimal exercise routine

coffee pot set up each evening, so I can fumble around and press a button at 5:30 a.m. the next day and coffee will come out

A constant that I am working on including, is drawing more. In my experience, I feel better when I make time to draw, but I’m still tinkering with how to set things up to be able to do that more easily. Putting constants into practice often takes experimentation.

Your constants start with your experiences: if something regularly energizes you or gives you hope for the future, that’s a good candidate to be one of your constants.

The key is to observe what consistently makes you feel better physically, mentally, and spiritually, when you do it. It is important to do your constants first, to make them your top priority. This is what enables you to tackle the variables with more grace.

Constants Do Not Always Have to Be Routines

Constants often involve routines and habits, but they are more than that.

Some years ago we were going through a financial crisis: a combined perfect storm of massive medical bills and being self-employed. It was not a given that we would be able to keep our house. Every mortgage payment was a nail-biter.

One of my constants during those years, paradoxically, was to keep a bottle of champagne in the refrigerator at all times, chilled and ready to pop.

“Should” I have been buying bottles of champagne when I was wondering if we could pay the mortgage?

Is there a financial advisor alive who would have said, “Anna! Pro tip!! When you are arguing with debt collectors, be sure to put champagne on your grocery list!”

This is what I mean by constants being so personal.

Seeing a bottle of champagne waiting in the refrigerator gave me a sense of hope that we would get good news someday.* It also drew my attention to bits of good news when they came, because then that was an excuse to pop the champagne! Seeing that champagne bottle waiting in the back of the fridge helped me to stay afloat emotionally, and eventually things got better.

Constants can change over time, as you and your life change. Maybe for a season, a constant for you could be having fresh flowers on the kitchen table (I would love to have that as a constant; but my naughty cats eat them**, and none of us like going to the vet.) .

Figure out your constants. What in your experience makes your day better, if you do it, or if you have it around?

Write them down. Then you know what’s a real priority for you, and what is not; and it will amplify your own voice beyond all the ones saying what you “should” do.

Don’t worry about others’ opinions. As you are able, do the things you know give you energy and hope.

References

Re low-income housing: This church razed their building and donated their land to provide housing for low-income seniors. It took seven years.

Church, S.P. on-the-H.E. (2021) ‘Breaking New Ground’, St. Paul’s on-the-Hill, 12 August. Available at: https://stpaulswinchester.org/2021/08/11/breaking-new-ground/ (Accessed: 17 February 2022).

Star, J.J.T.W. (no date) Planned senior housing complex gets $1.6M boost, The Winchester Star. Available at: https://www.winchesterstar.com/winchester_star/planned-senior-housing-complex-gets-1-6m-boost/article_97295492-e8ed-500b-b4b6-dcf30613c717.html (Accessed: 17 February 2022).

Cohen, D. (2015) Churchill Couldn’t Handle His Money, The Atlantic. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/01/why-winston-churchill-was-so-bad-with-money/419094/ (Accessed: 17 February 2022).

What Houseplants are Safe to Have Around Cats? (no date) The Spruce Pets. Available at: https://www.thesprucepets.com/houseplants-safe-for-cats-4798542 (Accessed: 17 February 2022).

Notes

*Churchill said, “I could not live without Champagne. In victory I deserve it. In defeat I need it.” But we weren’t Churchill; in defeat we couldn’t afford it. Come to think of it, neither could he…

**Our two scamps make me laugh every day, but they are the most badly behaved cats I’ve ever had. Thankfully, they use scratching posts and litter boxes, but they shred my papers, they knock things over and run away, and they eat my house plants, which are all cat-safe varieties now.