Draw Your Demons

In her “autobifictionalography” One! Hundred! Demons!, cartoonist and teacher Lynda Barry wrote and drew a story about how this book began:

“[The author] was at the library when she first read about a painting exercise called, “One Hundred Demons!” The example she saw was a hand-scroll painted by a Zen monk named Hakuin Ekaku, in 16th century Japan. (…) She checked out some books, followed the instructions, and the demons began to come. They were not the demons she expected. At first they freaked her, but then she started to love seeing them come out of her paintbrush. She hopes you will dig these demons and then pick up a paintbrush and paint your own!” (Barry 2017, pp 8-13)

When we take something that haunts us, and give it a name and an image, we can begin to free ourselves from it.

Consider the vivid image of the “hungry ghost” from Buddhism: the name, “hungry ghost,” and the image (a being with a narrow neck and giant stomach, whose cravings can never be satisfied). A wordless, image-less emotional experience — the sense of never feeling satisfied, always needing more; the inner gnawings of craving, addiction — is captured in a name, and in a picture: the “hungry ghost.”

Once you have a mental handle to grab back at what’s grabbing at you, then you can wrestle with it.

This is why naming and portraying something for ourselves is so powerful. We can stand apart from it, say, “Ah, there you are, you are showing up today, I wonder why?”

We can be mindful, instead of mindless about it. When we take inchoate emotions and put them into words, put them into a drawing or a painting, we get a grip on them, we get a mental handle to grasp them by. We gain new insights and awareness when we can name something, and picture it. We regain perspective, and self control.

Barry recommends painting your own demons with an inkstone and brush, like the Buddhist monks (and, bonus, she gives instructions on how to do this at the end of the book).

I also tried drawing some of mine.

That works, too.

What Hijacks Your Attention?

In the East and in the West, demons are spiritual parasites.

They feed on your life energy, optimism, perspective, and hope. They lure your thoughts and energies to swamps of anger, resentment, rumination, and regret. When we are unaware, unconscious of our personal inner demons and monsters, this emotional hijacking can lead us to let our inner trolls run the show.

But you can take away much of their power by drawing or painting them: capturing them in an image. By giving them a name: capturing them in a phrase.

This will help you become aware of when they are activated, trying to yank your chain to pull you back into the swamp.

Wisdom comes in part from coming to know yourself: not just knowing yourself in the career counselor sense, knowing your gifts and skills and strengths; but especially from knowing the unlovely, unloved things that pull at your psyche and wake you in the night.

In One! Hundred! Demons!, Lynda Barry wrote a story about “Girlness:” a child longs to have girly things — frilly dresses, a beautiful doll — but is scolded and ridiculed by her mother, who had grown up in wartime, and said that little girls who had such things were spoiled.

At the end of the story, as an adult, a surprising encounter opens the way for the narrator to delight in something unabashedly girly; something she had long believed was not for the likes of her.

We cannot destroy our own demons, or our shadow side, or the things that haunt us. The drive to purify, the illusion that we can rid ourselves of that which we don’t want to claim, is its own kind of demon.

But we can become more conscious of these parts of ourselves. We can grow in awareness of how these parts get activated and how they affect us.

This gives us more wisdom about how much power we give them.

To name something is to gain power over it. To create an image of something is to gain power over it. When I draw a demon, it can no longer swamp me so easily, because now I can grasp it. Now, I can wrestle back.

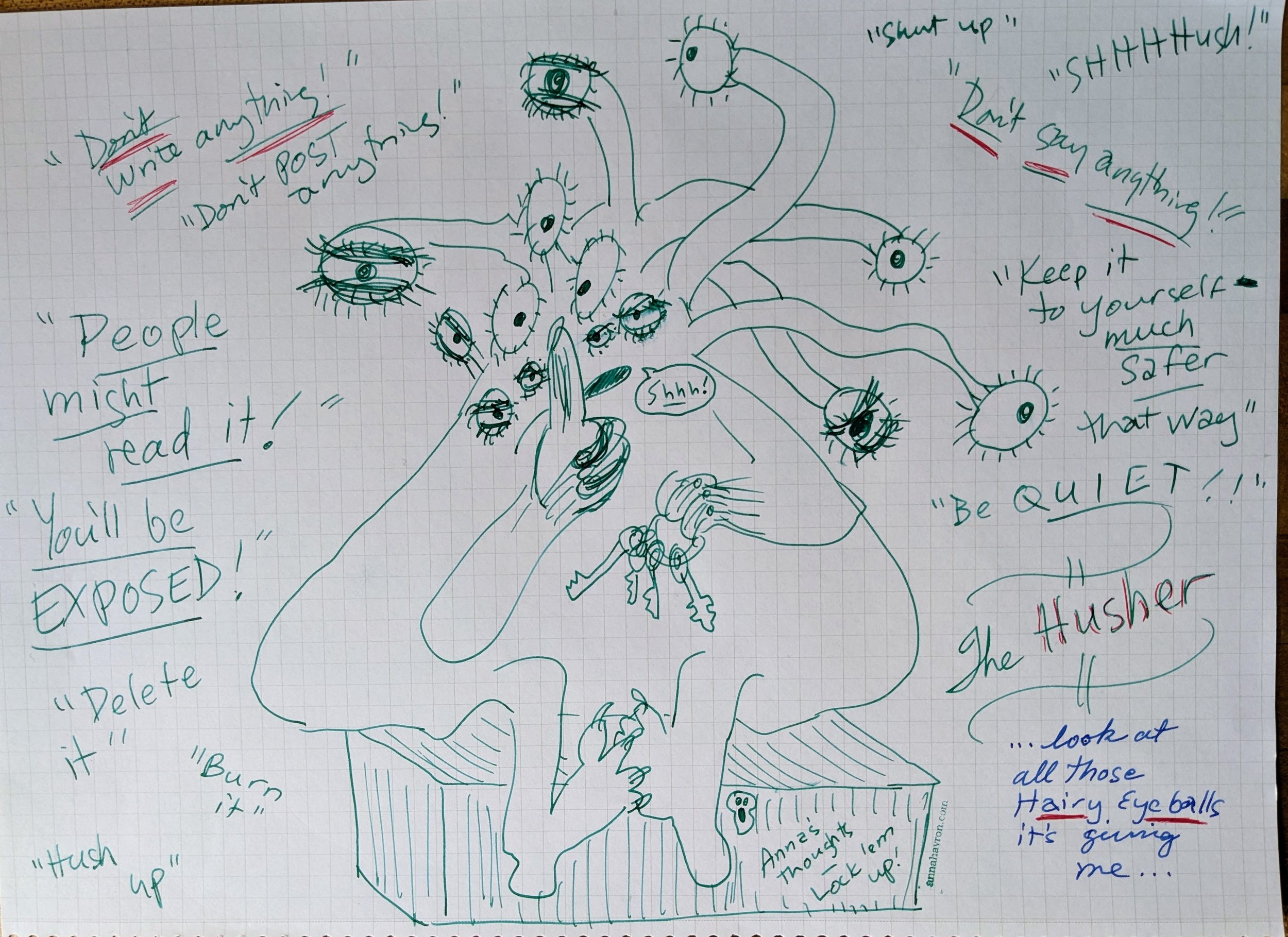

“Ahhhh,” I say to myself, when I am afraid to write or to publish something (like this post!). “Here comes the Husher! Shall I let it tell me what I can write?”

A strange thing happened as I began to paint and draw my demons, and to write down what they were saying.

Many of them made me laugh, when I saw them on the page. And laughter is power; especially over demons.

But a more surprising thing happened that I did not expect at all: I began to feel affectionate towards them.

Some of them are trying to protect me.

Others of them, once I draw them, have much less power than they had when I was unaware of them. They threw big shadows that scared me, but they look much smaller on the page.

And some of them seem glad to be known.

Some of them seem to have been waiting for me to come to my senses. Some of them, once I draw them, seem to say, “At last — very good, now you can see me; my work here is done.”

And some of them are actually others’ demons, which were piggybacking on my shoulders until I twisted, and threw them off onto a page.

I wonder if the “Girlness” in Lynda Barry’s story was more the mother’s demon than the child’s. Nevertheless it rode the child well into her womanhood, whispering, “You can’t have things that delight you; you’ll be spoiled, you don’t deserve them.”

Try It Yourself

Drawing or painting brings up insights that will not come to you in words. I always get surprised by the imagery that comes up when I draw these.

With the Husher, I set out to draw a lock on the box that the Husher is sitting on; but instead my hand drew a little skull.

I didn’t plan that; but it certainly gets the message across that it is deadly for my inner life if I obey the Husher and refuse to allow myself to write and draw.

Another thing I learned from Lynda Barry: draw as if you were a small child. Make marks on the page, draw or paint loops and lines and scribbles and see what emerges.

Narrate as you go, or narrate what it is after you’ve drawn it. This is how small children draw. Little kids make words and drawings together. They draw, and narrate while they draw.

Little kids are also not worried about whether their artwork is “good.” (That’s a demon that older folks hoist on young shoulders.)

If right now you are saying to yourself, “But I can’t do that,” then QUICK!

Draw that one!

That’s your first demon, you’ve spotted it in the wild!

Pretend you are four years old, and remember that no one has to see your drawing but you. Draw the one that tells you that you can’t waste your time drawing your demons, or it’s stupid to do this, or that your drawing isn’t good enough.

Draw it down, capture it on the page. Write down what it’s saying, about why it thinks you cannot, or should not do this.

Why doesn’t it want you to draw it?

Find out.

Drawing these things feels great!

Drawing my demons has been one of the coolest and most helpful things I have done. It’s also a lot of fun.

Whenever I draw one, I get a grip on it: I can then decide whether or not I will keep mindlessly obeying it; I can then decide how much time, attention, and energy I will keep feeding to it.

It makes me feel more alive. It frees all kinds of creative energies.

Try it.

See what shows up on the page.

I bet you will be surprised.

Copy and share - the link is here. Never miss a post from annahavron.com! Subscribe here to get blog posts via email.

References

De-Conditioning the Hungry Ghosts | Psychology Today (2017, 5 September). Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/finding-true-refuge/201709/de-conditioning-the-hungry-ghosts (Accessed: 3 March 2023).

Barry, L. (2017) One! Hundred! Demons! First Drawn & Quarterly Edition. Drawn & Quarterly.

Resources

Lynda Barry was named as a MacArthur Fellow in 2019. She has written several books about how to draw and write, especially for those who think they cannot do either. These books are also thought-provoking meditations on images and memory. Here are two of my favorites:

Barry, L. (2008) What It Is. Drawn & Quarterly.

Barry, L. (2014) Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor. Drawn & Quarterly.